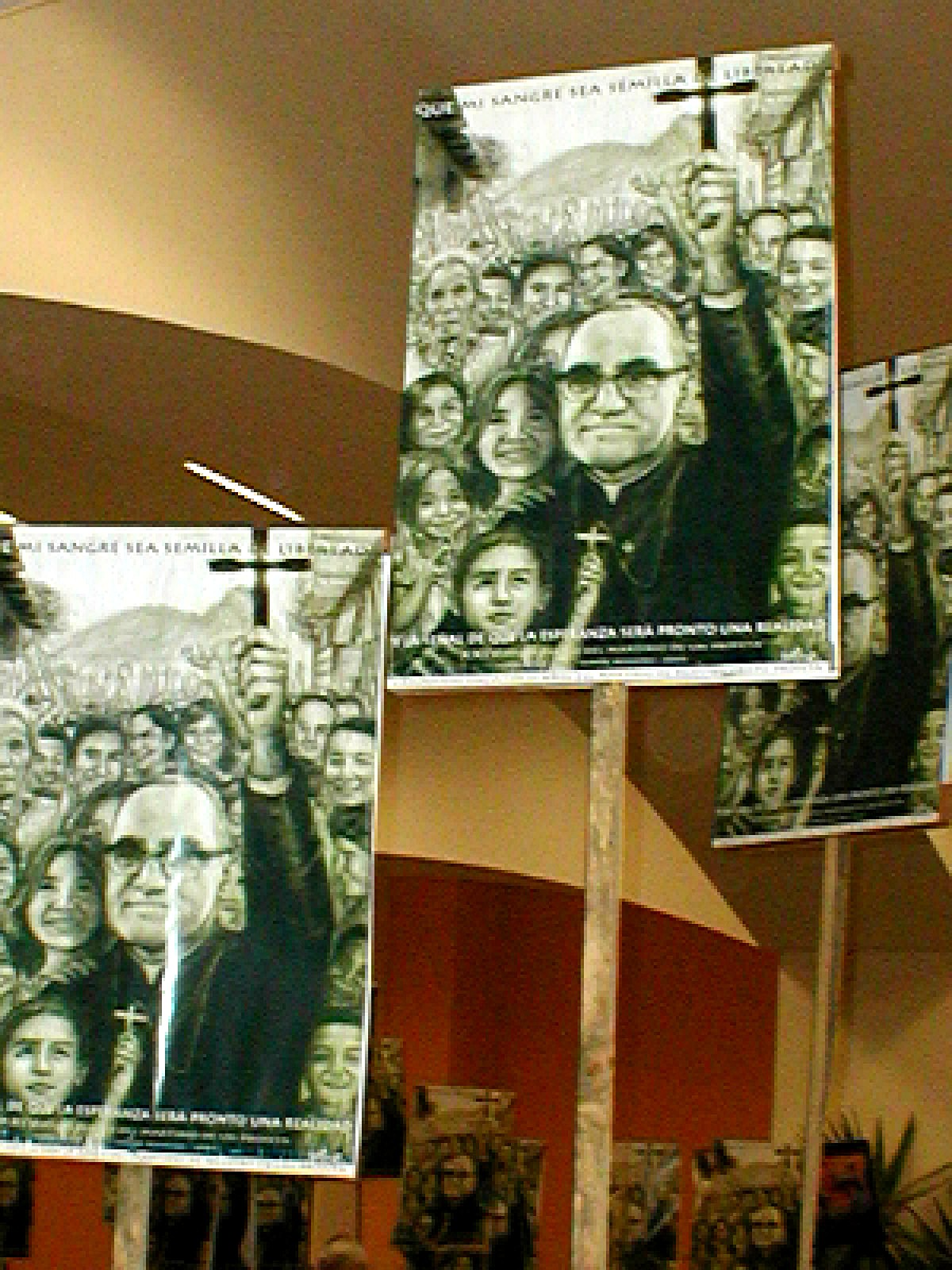

Romero is buried in the basement of the cathedral in San Salvador. It would be a stretch to describe this as a crypt, since mostly, it’s a basement meeting room, but a few others are also buried there with the archbishop. Right after his death, church officials could see the tremendous outpouring of devotion to Romero’s memory, and decided it would be best to bury him in a more out-of-the-way place than the main floor of the sanctuary. So they settled on the basement, but almost as soon as they did that, groups began to hold popular Masses, with folk music and liberation preaching, around the tomb. Eventually, an altar was built, and attendance at the popular Mass began to outstrip that of the more conventional worship going on upstairs. Early in the week, we go to visit the tomb during a rally of Christians from many parts of the country. Many people in the audience have posters and signs that they’ve made, some of them real works of art. Groups of musicians play and many troupes dance. People clap along and hold their signs high as the speakers talk about the archbishop’s legacy. On the flat, plain surface of the tomb itself, people scatter paper flowers, notes in envelopes, and handmade plaques on the polished granite. As I stand looking at the tomb, two women come and begin to collect the notes and flowers in a basket, making room for the next wave of devotion.

The Saturday after Easter is the big day in this week of commemoration. We go early to the cathedral, expecting to find a scene very similar to the one we saw earlier. But today, the atmosphere is completely different. The current archbishop is seated at a long head table, flanked by his fellow prelates. We hear that the monsignor arrived in the morning unexpectedly, and announced that he would be leading the day’s program. He brought another surprise with him: an elaborate, carved cover for Romero’s tomb, commissioned in Italy by the archbishop for the anniversary. On it, Romero’s effigy is surrounded by four women, who each hold one of the Gospels in their hands. The surprise commission is a good example of the tensions between the two camps of the Roman Catholic Church in El Salvador. On the one hand, the archbishop commissions a tomb cover for a man he does

not necessarily admire, because he realizes Romero’s still-growing importance for many Catholics throughout Latin America. In some polls, only 58% of Salvadorans call themselves Roman Catholics if there’s an option to call themselves “nothing.” So the archbishop of San Salvador cannot afford to alienate the many faithful who direct their piety to Romero. The tomb cover could be a huge gesture of goodwill as well as politically savvy, but it’s not, because many Catholics who consider Romero a saint have been trained in the way of Christian base communities, where a major step like this commission is decided by many, not just one man. There was no consultation between the archbishop and the Romero Foundation, the group that administers his legacy, about the wisdom of a cover versus some other gesture, no communication about who the artist would be or what the cover would be like. There wasn’t even an advance notice that it would be placed on the tomb on the morning of the Mass. The gulf between Salvadoran Catholics is still very wide.

But the conflict earlier in the day doesn’t keep Salvadorans away from the big outdoor Mass and procession in the evening. We worship with several thousand in a plaza in downtown San Salvador as evening falls. The wind begins to pick up, and it blows out our candles, even in their tall paper lanterns. It’s actually chilly. The music is tremendous, The Mass for El Salvador by Guillermo Cuellar, who composed a lot of music as a young man for Romero. The sermon is long, and I can’t understand it. I finally sit down on the pavement. At knee level, I can see how many parents have come with young children. Many stand throughout the whole service cradling infants and sleeping toddlers. We wonder what will happen when it’s time for communion, but indeed, dozens of communion ministers fan out to the far reaches of the crowd with the bread of life.

It takes a long time for the movement of the procession to reach us; ten thousand people are marching to the cathedral. When we reach the square in front of the cathedral, several thousand more are waiting there. A huge banner with Romero’s image on it has been raised, covering the entire front of the church, the equivalent of four or five stories. As I stand among the crowd, I find myself wishing that I could have been part of the crowd that stood out here twenty-eight years ago, not at Romero’s funeral, but at another funeral, the service for Rutilio Grande. I reflect on what Inocencio Alas said about that day, that he watched Romero cross the threshold and walk through the door. The people who saw Monsignor Romero’s conversion on that day witnessed a moment that was so significant that twenty-eight years later, it’s just as unbelievable and inspirational as it was then. When the Vatican asks what miracles potential saint Oscar Romero performed, I hope that irrevocable moment of sacrificing his privileged life for his fellow Salvadorans will count.