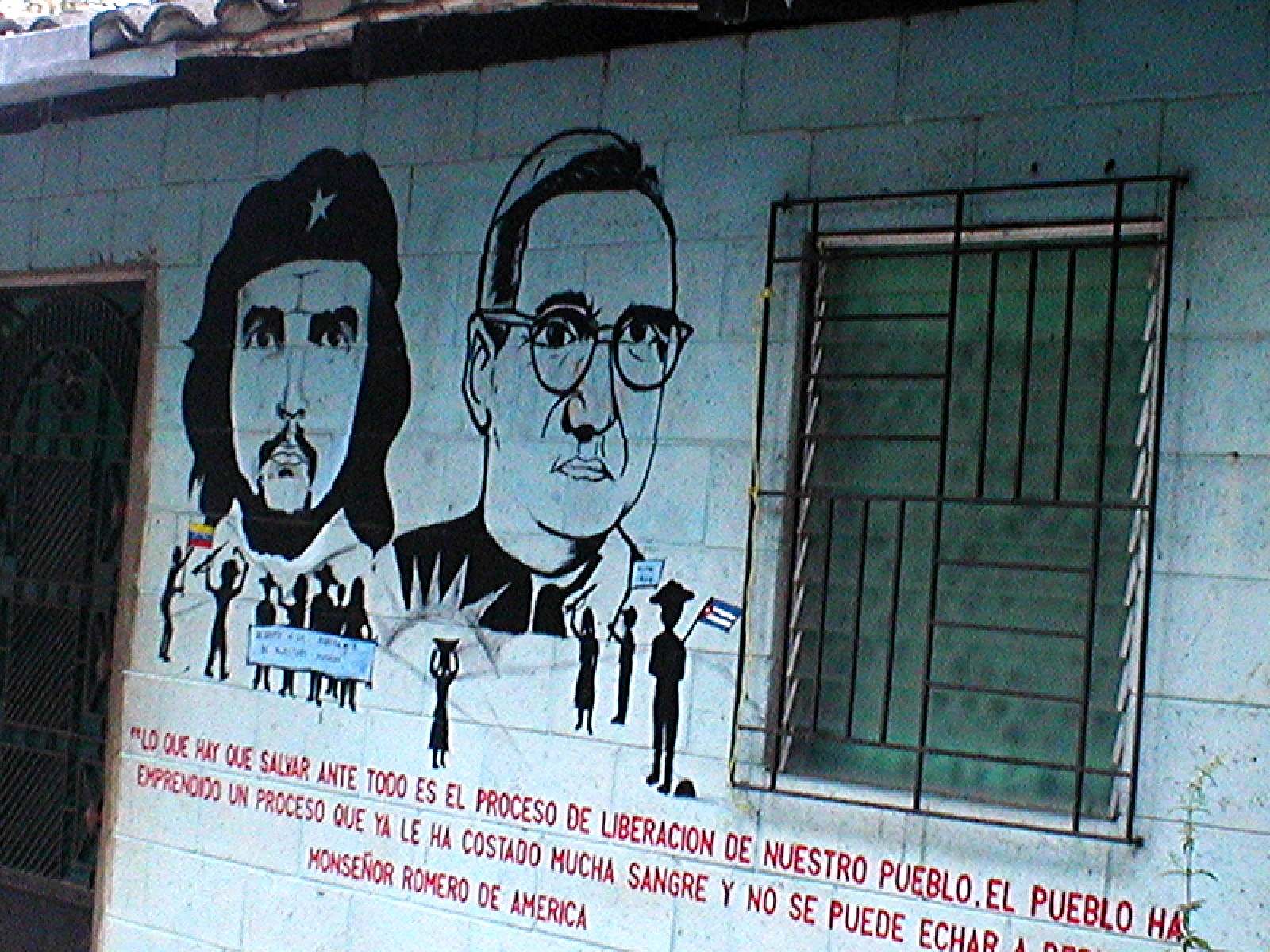

Romero’s legacy is complicated – Vive Romero, Vive! Viva international solidarity forever, Viva! Everywhere we visit, we see the slain archbishop’s image alongside the images of very different Latin American heroes, like Che Guevara and Farabundo Marti. These side-by-side portraits are a shorthand for some of the deep divisions in Salvadoran society, and I wonder what Romero would say seeing his image paired with those of Guevara and Marti. Marti was a Salvadoran who emerged as a labor leader in the 1920s. Like so many in every part of the world in the 1920s, Marti was interested in Marxist principles, in his case, how they might be used to organize farm workers. At the same time, the ruling elite in El Salvador, The Fourteen Families, as they were known, were equally interested in the rising Fascist movements in Germany and Italy. It’s hard for us in our own time and place to understand the deep attraction that both Communism and Fascism had for so many at the beginning of the century, but in the 1920s, both seemed boundlessly hopeful and wonderfully fashionable. Ladies in England liked to wear fancy Fascist buttons on their dresses at tea, and American magazines wrote gushing articles about a rising Germany, Adolf Hitler. Many immigrants to the United States, especially from Scandinavian countries, turned around and went back the other direction, to Russia to join the Soviet revolution. Just as those two forces clashed in so many places in the 1930s, so they clashed in El Salvador. In 1932, Marti was killed by the newly-installed military government, along with 30,000 other Salvadorans, in a massacre now known as La Matanza, or simply, The Massacre.

By the 1970s, the United States was giving massive military aid to the military dictatorship, because its revulsion of the Left was greater than its revulsion of the Right. The Roman Catholic Church felt itself to be in the same predicament, and followed the U.S.’s lead. But then liberation theology began to develop momentum throughout Latin America. Its emphasis on the majority poor sounded like the Gospel of Jesus Christ to its followers. That same emphasis on the majority poor sounded like the Marxist rule of the proletariat to those of the political and ecclesiastical establishment. The proponents of liberation theology saw themselves offering a third way that went beyond political manifestos. It was a way that required courage and risk, however, and that was not very attractive to an ambitious churchman like Oscar Romero.

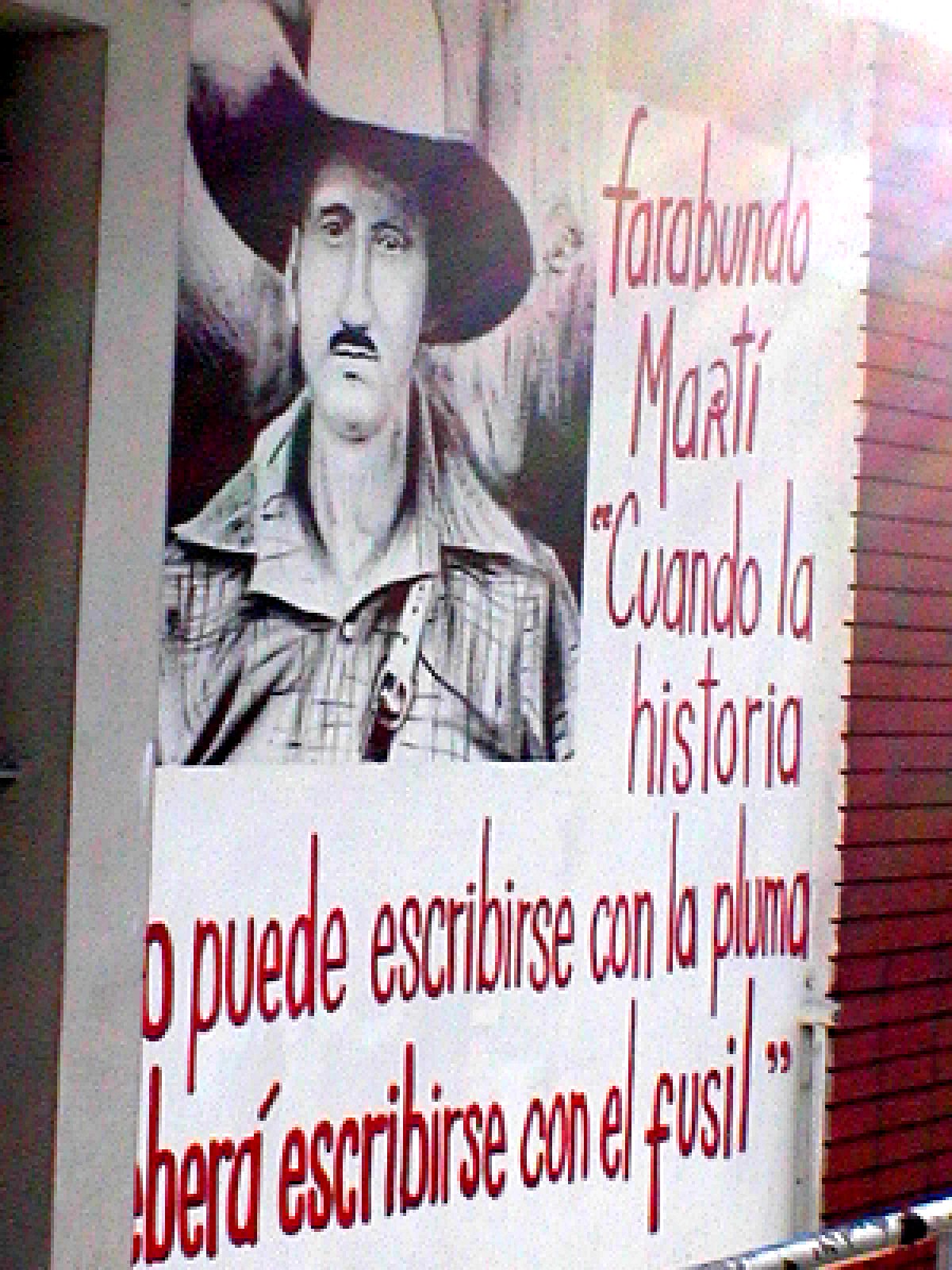

This mural of Farabundo Marti, on the wall of a building in San Salvador, is opposite a companion mural of Oscar Romero. This one reads, History is not written with a pen but a gun

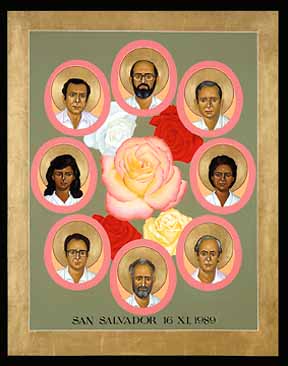

In 1989, six Jeusuit priests, their housekeeper and her teenage daughter were killed in the garden outside their quarters at Jesuit University (top pictures); a painting of them hangs in the church where Romero was killed; an icon of the martyrs (right)